There is no convenient sovereign cloud

For years, Europeans have lived comfortably, storing and processing data on servers located in the EU, i.e. on servers physically in the EU, but legally controlled by foreign entities. We celebrated compliance audits and built data centers across the continent, believing that physical location equaled digital safety. But what good is data residency compliance if you cannot be certain you can access your data tomorrow?

The Sovereign Lie

Usually, when we talk about sovereign cloud, we tend to think in terms of confidentiality. Can someone get to our data? Let’s store it on a public cloud server in a data center in the EU, then it will be safe and the compliance folks will be happy. There were concerns with this approach, so the providers introduced the so-called sovereign clouds to protect their market share:

Seemingly the same cloud, but sovereign. True sovereignty requires complete independence. A US tech company selling a ‘sovereign’ cloud in the EU is a contradiction in terms. Often the wording is chosen carefully, such as ‘operational sovereignty’ - maybe the operations are independent when Azure is deployed on-prem, but there is no control over the supply chain security and this is somehow conveniently forgotten by the marketing and sales teams, and their clients. In reality, the US CLOUD Act overpowers any local regulations - the US can force any US-based cloud provider (or their foreign subsidiaries) to disclose data, no matter where the data is stored. Jurisdiction follows the provider, not the server - data residency doesn’t matter. This directly conflicts with the GDPR requirements and renders the aforementioned sovereignty claims useless. Thorough analysis has been done on this topic - I recommend the report for the German Federal Ministry of the Interior for a deep dive. It’s worth noting that it is not just the US - China has a similar law, which can force companies to hand over data collected outside China.

US hyperscalers attempt sovereign washing and even though it backfired under oath, their efforts are maintained nevertheless. E.g. Microsoft’s partners are encouraged to specialize in Digital Sovereignty - here is the learning path in case you are interested. This blog post repeats the narrative. AWS even established a separate entity to muddy the PR waters, while pretending the Cloud Act doesn’t affect its subsidiaries. Besides the regulatory misconceptions, the obvious must be stated: those sovereign cloud products are fairly new and considering that the public concern in Europe is growing, the demand is likely not sufficient to offset the development costs. As a result, some sovereign clouds lack features that you are used to in global clouds, and simply switching to a ‘sovereign’ endpoint will break your workflows. Don’t be surprised if a solution architect advises against the sovereign cloud way, if you are not obliged to use it.

Governments spying on each other and their citizens is not something we haven’t seen before. Fern has recently published an excellent documentary on NSA’s Spy Hub, the 33 Thomas Street Building, which started tapping lines 50 years ago. In 2003, when faced with public outcry because of mass surveillance (wiretapping without a warrant) concerns, US renamed its Total Information Awareness program to Terrorism Information Awareness. The Snowden files revealed you don’t have to be a terrorist for NSA to keep an eye on you - German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron found out the hard way.

The Kill Switch: It’s Not Theoretical Anymore

If confidentiality is not a given, what about availability or in the event of an unavailable cloud, the increasing dependency for core services? Consider how availability shapes policy making, while Big Tech strengthens its grip on our society. Unavailability can be either intended or not intended. Recent years were eventful in both cases. As easy as public cloud scales, it can also scale down. Not intended global incidents like Azure, AWS and Cloudflare displayed clearly how dependent many services are. Downdetector now has its own downdetector. If your web application is not stable, just generate a fake Cloudflare error page and blame it on them. Intended unavailability happened on a smaller scale, though it was enough to give food for thought:

- Six judges and three prosecutors at the International Criminal Court have been sanctioned by the Trump administration for calling out the genocide in Gaza and issuing arrests warrants. Being sanctioned by the US means that you are cut off from the banking system and US companies must close your accounts. You cannot even book a hotel in Europe through a US intermediary website. Microsoft has blocked the email accounts of ICC members and later denied doing it. This resulted in ICC switching to the German office suite Open Desk. For context, the ICC is recognized only by a part of the world as a court and considered a rather political instrument. E.g. China, Russia, the US and India do not recognize the ICC - this limits its impact drastically. Of those superpowers, only the US has the ability to effectively impose sanctions if the ICC does something that does not please the US. Given that the ICC has not been recognized by the US since George Bush, it is weird that such an international organization still had core suppliers in that country.

- YouTube has deleted the account of an independent British journalist.

- The Amsterdam Trade Bank, which was partially owned by Russian oligarchs, had to declare bankruptcy even though it was solvent, as Russia invaded Ukraine and the sanctions forced Microsoft to block the accounts of all employees. The bank also lost access to payment systems.

The Munich Saga

While it’s easy to go into the solution mode and debate how to fix the current situation, looking at few cases helps to understand what we’re dealing with in terms of vendor lock-ins and strategies employed by providers to win and/or keep the market share. Germany is interesting to start with, as their view on data, and who can access what and why, is stricter than that of the rest of the world. This applies not only to the government but also to the citizens themselves.

In 2003, the city of Munich was the first to attempt freeing itself from Microsoft’s grip. The project, coined LiMux, aimed to migrate 15,000 workstations to Linux and LibreOffice and was successfully completed in 2013. Christian Ude, Munich’s mayor at the time, supported the project for more than a decade. Back in the day when the decision to migrate to Linux was first made, he was famously targeted by Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer and Bill Gates:

- Steve Ballmer, who called Linux a cancer, attempted to win Ude over by offering a large discount on licensing costs, though it is unknown for how long those licenses would be discounted. Supposedly, Ballmer even sacrificed his ski trip in Switzerland to visit Ude in person.

- Bill Gates gave Ude a ride from a conference to the airport in his limousine solely to talk to him about his motivations behind choosing free software.

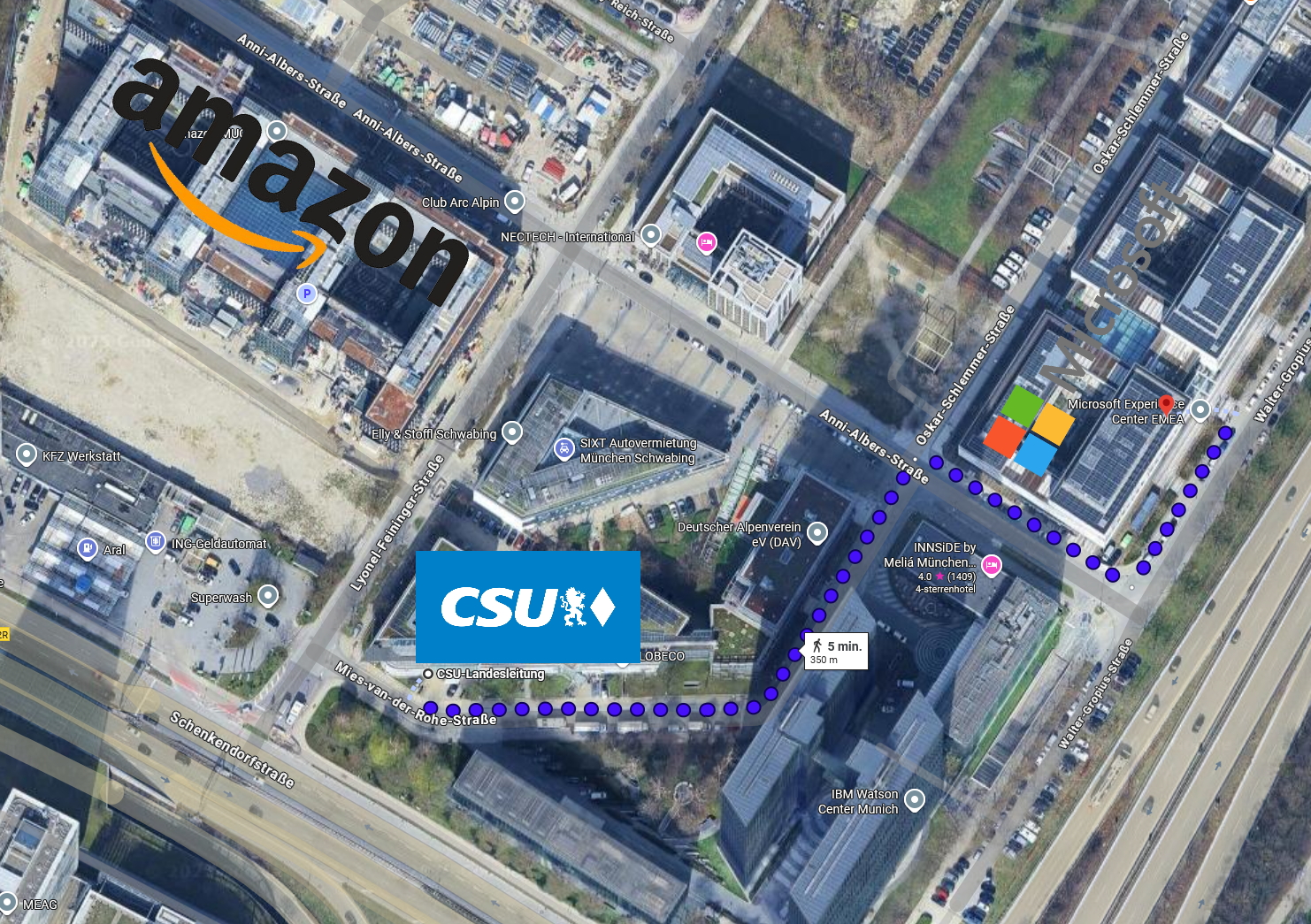

Christian Ude was a problematic mayor for Microsoft, to say the least. In 2014 Dieter Reiter assumed office as mayor of Munich. Before the election, he happened to refer to himself as a Microsoft fan. Not surprisingly, Reiter was also against open-source software. In 2017 Munich witnessed a change in strategy - the city council voted to return to Windows by 2020, i.e. to create a Windows 10 client. This decision was rather political. Allegedly, as part of the deal Microsoft was to move its German headquarters to Munich, which it did. Reiter, the new mayor, helped with the move and was proud of his involvement. Fast forward to 2020, Munich’s newly elected officials believe in the principle of public money, public code and take a U-turn: the city will use open-source software after all.

Very conveniently, Microsoft placed its headquarters just next to the headquarters of the CSU, Germany’s biggest party at the time.

Additionally, Microsoft has an office in Berlin , which is seemingly only dedicated to lobbying, and they are very honest about it on their main page:

"In the heart of Berlin, we bring digitalization to life and engage with current issues in digital policy. This makes Microsoft Berlin a meeting point for anyone interested in politics and technology."

In November 2025, Amazon has opened its new MUC21 office just across the street. It’s hard to pinpoint the exact date, as no official press release about this can be found, but there are multiple LinkedIn posts from people happy to work 5 days a week from their new office.

The physical proximity of these headquarters to Germany’s politicians underscores the lobbying weight US hyperscalers place on politics - influence that European providers might struggle to match.

Google isn’t sitting quietly either. In September 2024, it launched an Experience Center in Munich - the Google Cloud Space has 900 m2. The market needed sovereignty, and Google is here to save the day - their first Sovereign Cloud Hub was opened last year and celebrated by hosting the Digital Sovereignty Summit. Google mentions it’s co-located with an existing security hub, so this looks more like a rebranding than a new investment.

There is of course nothing wrong with the marketing machine of big companies doing its work, but the narrative is of questionable character - especially when you compare the PR measures of Microsoft, Amazon and Google to the relatively limited resources, knowledge and power European players have. On one hand it is understandable that those providers are trying to respond to our market needs - it’s a chunk of their revenue - but on the other hand, just being honest about the legal limitations is also an option.

I do wonder what the location criteria of Microsoft, Amazon and Google are, when they pick one for a digital sovereignty experience initiative. For instance, Germany and France are proactively investing in autonomy, with examples such as OpenDesk and OpenCode from the German Center for Digital Sovereignty, or the French La Suite Numérique for the civil service. These are developed as open source and available in English. The French state allowing its software to be developed in English is extraordinary.

Beyond Munich

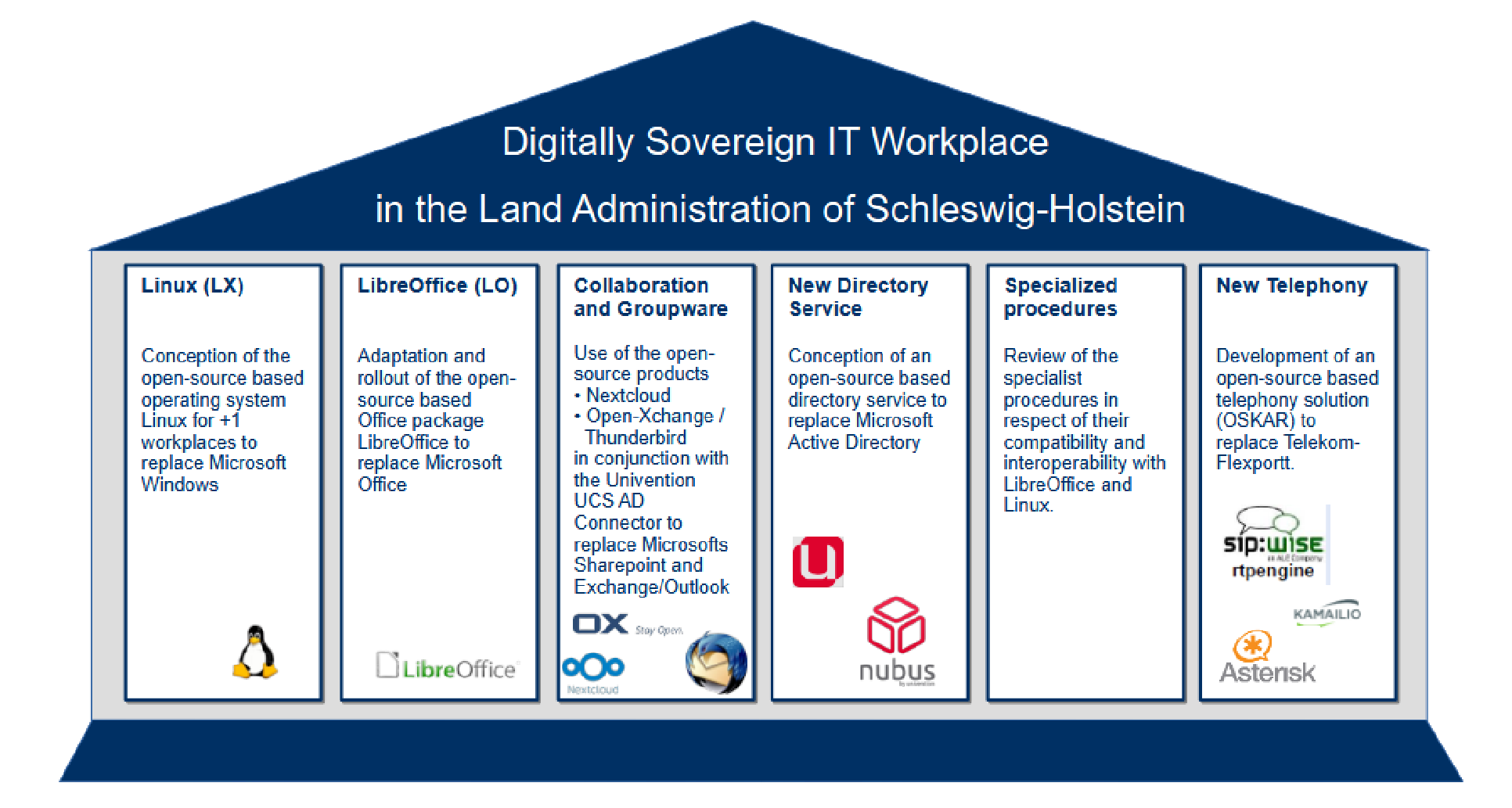

The German state of Schleswig-Holstein has been working on a Microsoft exit since 2021 and has so far successfully offboarded Exchange and Outlook, i.e. 40,000 accounts. There’s appetite for more - the rest of the Office suite and Windows are next. It is a truly great initiative - it takes courage to launch something like this. Breaking the hegemony of Big Tech is impossible, yet at the same time highly desirable. Their strategy is published here. It includes a beautiful overview of the key pillars, much like the Well Architected Framework of any non sovereign cloud provider.

Please note, this state did not pick a few open-source solutions to implement without a second thought. The state has an enterprise version of Nextcloud and they collaborate with Nextcloud to prioritize specific functionalities, which drives among others Nextcloud’s AI strategy. They use a version of LibreOffice powered by Allotropia to have enterprise level support. Their Nextcloud integration is based on Collabora Office Online, and is also supported by Allotropia. If you do it, you have to do it right. Even partially using Microsoft products means you will remain stuck with interoperability issues. Only by adapting your ecosystem you become the one that calls the shots. If you adapt your organization to Microsoft’s ecosystem, they determine the rules and the costs.

Recently, Denmark has declared that their government will ditch Microsoft in favor of LibreOffice and Linux - a move rather unsurprising considering Trump wants to own Greenland. If Denmark was to be sanctioned due to being too reluctant to give up their control over Greenland, they can wake up with no access to their email tomorrow, just like the ICC did. In Austria, the Austrian Armed Forces migrated 16,000 workstations from Microsoft Office to LibreOffice. Austrian Ministry of Economy migrated 1,200 employees to Nextcloud, though some critique this move as the operations are supported by Atos, an IT services megacorp with financial issues.

While some find a way to break free, e.g. the Dutch government sticks to M365 as they were not able to find a suitable alternative, publicly acknowledging the inconvenient, growing dependency. It’s not like they suddenly realised there’s a problem - the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security had issued already warnings twice, once in 2019 and the second time in 2022. So what went wrong in this case? They inflicted this situation upon themselves. E.g. if the Dutch government had stuck to their self-imposed standards and used ODF, document formats and the associated interoperability issues wouldn’t be such a problem. Some of their solutions natively support the ODF format, but people use OOXML simply because it is the default in Microsoft Office. Everyone does it, so why shouldn’t we? Often people simply don’t know any better.

Microsoft, being no stranger to vendor lock-in practices, turned OOXML, a pseudo-standard that pretends to be open, into an ISO standard through various lobbying efforts and a fast tracked ISO process, which helped to bypass objections voiced by opposing members. Though they admitted openly that offering to reward partners for joining the bodies deciding on ISO recognition of OOXML was a mistake:

- Controversy Mars Swedish OOXML Vote

- Microsoft accused of rigging OOXML votes

- How the Swedish OOXML Vote Was Bought for $57,000 In 2001, Microsoft lost an antitrust lawsuit, known as United States v. Microsoft Corp., which condemned the bundling of Internet Explorer with Windows. Today we see the same patterns with applications that can only be opened with Edge. Even if you try to uninstall Edge, it will be back with the next update.

Often the argument is made, that even though a government department would like to use ODF, this would cause issues with the collaboration with external parties. However, as a government, you can and should require your suppliers to deliver documents in ODF, even if those suppliers work with Microsoft products. The human element unwilling to change is the only limitation. LibreOffice has significantly improved its support for OOXML, if you must use it. Though OOXML support is maintained to facilitate transition. New documents should be ODF, as the OOXML standard contains built-in Microsoft-only functionality that other solutions cannot handle. Even if compatibility is claimed, often only a subset of OOXML is supported.

The Education Loophole

When we take a look outside of the enterprise world, it is hard not to notice that the education sector is heavily targeted. Stimulating adoption at a young age and getting children used to your ecosystem makes a lot of sense from a business perspective. So much, that the Office packages are heavily discounted. This wouldn’t be so bad considering it is done under the pretext of enabling the education sector, but the schools and universities are left with the responsibility of managing the users like they are an enterprise. Often they are not aware that they should handle e.g. data insight requests and scholars end up in a loop being sent back and forth between Microsoft and their school. There’s some pushback in Austria against this issue. Austria’s data protection authority found that Microsoft was tracking students and that Microsoft must provide users access to their personal data, not to shift all the responsibility to local schools. The Warsaw School of Economics (SGH), a Polish university, deploys desktops with a default desktop background, which displays ‘Microsoft - SGH: Partners in Digital Transformation’. It seems they don’t have the sovereign package yet.

The Polish government has recently partnered with Google to develop AI capabilities. For the education sector, this means:

- access to Google Workspace for Education for everyone,

- Google AI training for 30,000 teachers,

- an update to Chrome OS Flex for 200,000 devices.

Somewhat worryingly, the supposedly strategic partnership includes consultations of the use of AI in schools, as well as the analysis of data concerning device usage in schools. Google has also joined forces with SGH, and launched The ‘Skills of Tomorrow: AI’ campaign under the honorary patronage of the Ministry of Digital Affairs, which was a PR success. It was a ‘free’ 5 weeks course after all. While it’s beneficial for everyone that people have learned new skills, the downside is that those are rather Google AI skills, not just any AI skills. Google has also partnered with Kaggle and launched together a 5-Day Gen AI Intensive Course, which I have attended. The technology is great, but the sovereignty gap is widening. Vendors are increasingly aware of the power of a skilled workforce - after all, even if you have the greatest technology, companies need people who are capable of using it. Any course that is offered for free by a vendor, is not free - you pay with your time and the missed opportunity to learn something else, perhaps something vendor agnostic. Getting thousands of people certified in a product increases mainly the value of that product, which gets easier to sell and to adopt by organizations, as they can find people with skills more easily and/or cheaper.

For instance, Microsoft has Microsoft Learn, the Enterprise Skills Initiative) (the same as MS Learn, but with live training) and Customer Connection Programs. Google’s alternative is called Google Skills, previously also known as Cloud Skills Boost, and has the additional benefit of hands-on labs on a free sandbox account in the GCP console, whereas Microsoft does not. AWS is an exception in this case. While they offer free foundational training, many features are hidden behind a paywall. In the CSP world, the larger your bill is, the higher is your budget to upskill your employees, i.e. have them attend courses and pass exams on the cost of the provider. This is a race to the bottom for employees: the more people get certified, the lower the value of those certificates. To compensate for the decreasing value there is no other way than to get more certificates. As this progresses, it becomes harder and harder to find independent consultancies that are capable of evaluating different, sovereign solutions. If everyone specializes in Microsoft solutions, it is unlikely they will recommend something else.

Established vendors have various advantages, one of them is using the momentum of existing customers to generate new ones. This is done by making the customer the hero. You convince a director (or someone with purchasing power) he or she needs your Zero Trust product to be resilient in today’s dangerous world. After the implementation, you put them on stage to present their transformation during your own conference, like a Data for Breakfast meeting or any local Azure, AWS day. Their peers see the success and buy. Rinse and repeat, and the director in question is even happy to do it: the exposure and the personal brand building offset the products’ shortcomings, which somehow were forgotten on stage. Prospects trust their peers more than salespeople, so you let your customer do the actual selling by sharing their transformation story.

The Way Out

When the topic of coordination of common software projects across the EU is raised, often there’s a dilemma to solve - should everyone own their own cloud, or can I trust my neighbours to develop a cloud together, so that we share the costs and the benefits? Perhaps a distributed model, in which countries collaborate on the software, but own their own data centers, makes the most sense. We need a federated model where a country can leave without crashing the system. We must acknowledge that both the EU and its member countries can change how they operate over time, thus there is no perfect answer to this. Especially, as social media algorithms serve the masses with content that generates outrage to maximize engagement with the platform. While this maximizes their revenue, it drives citizens apart either to the far left or the far right. For instance, in Myanmar, a military dictatorship used Facebook to help stir up a genocide. We have also had the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data scandal, which enabled micro targeting of US voters with customized messages about Trump during his presidential campaign in 2016. Regardless of the course of politics in the EU, it will benefit from its own technology. Even if entire Europe was to become a dictatorship, we don’t want to fear that sanctions can shut down our critical services, defense systems and the government.

The question of how to make it happen is not a question anymore - a letter from the industry is on the table, begging the EU for a commitment to sovereign infrastructure. The initiative is called EuroStack and has won the political support of Germany and France. EuroStack focuses on both physical and logical infrastructure, and proposes concrete measures so that Europe becomes more technologically independent across all layers. To quote a key proposal:

"Creating demand – industry will invest if there are adequate demand prospects. The business case for investment must be supported by clear, objective and strong procurement obligations - with a formal requirement for the public sector to “Buy European” – i.e. source their needs from European-led and assembled solutions (while recognising these may involve complex ecosystems and supply chains). The private sector needs appropriate incentives and inducements to steer a portion of their demand towards European suppliers enabling sovereign solutions."

The idea is as simple as stimulating appropriate demand, which generates cash flow to European companies, which in turn enables them to build out their technology over the years to come. Appropriate incentive for the private sector can be as simple as tax benefits for buying European products. While migrations are inconvenient, at the end of the day money is the deciding factor. If it is cheaper and more convenient to pay for not sovereign technology, then there is no business case to even consider switching. A last measure can be the regulatory way, though if implemented right away, currently many governments would need to fine themselves first.

The Battle for Infrastructure

One of the policy measures Europe could take is to block acquisitions of its critical companies by e.g. US companies. In November last year, Kyndryl had acquired Solvinity, which means that they now hold a kill switch for the Dutch digital identity, justice, regulatory, and intelligence systems, together with the ‘sovereign cloud’ of the City of Amsterdam. Ronny Roethof’s blog post explains this case in detail.

A blocker the Dutch government faces is the lack of space and capacity on the power grid to build more data centers. Even if they would like to invest in a sovereign cloud - there is no place to host it locally. There are more than 200 data centers in the Netherlands - should the government buy some of them back? Existing data centers also pose a difficult ethical dilemma - should anyone be able to use servers located in another country for whatever purposes they please? Israel has used a data center in the Netherlands for mass surveillance of Palestinians. Their phone calls were intercepted and analyzed - allegedly also used to identify bombing targets. This stands in stark contrast to the Dutch policy on the situation in Israel and the Palestinian Territories.

Another battle with no end in sight are the product bundles. If Teams can be sold separately, then it would be beneficial to have that option also for other products, which come together as a package. In terms of policing vendors, the case of Broadcom is one to keep in mind. Broadcom had acquired VMware in 2023 and increased the licensing costs exorbitantly to better their bottom line. For a Dutch government agency, the Rijkswaterstaat (RWS), that meant that their new subscription licenses would cost 85% more on a year basis. RWS wanted to migrate away, but Broadcom offered no transitional help. RWS took the case to court and won, setting an important precedent for other impacted customers. The court ruled that Broadcom must provide exit support (updates, patches, assistance) for up to two years or face penalties up to a max of €25 million. According to the court, Broadcom has a duty of care - they cannot just quit on their customer.

Also noteworthy, the European Commission is considering whether AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud should fall under the Digital Markets Act, which was e.g. used to force Apple to allow alternative appstores in iOS. A problem here is the user count. For a company like Meta or Apple, it is relatively easy to determine their impact in terms of active users, but for a business service like Azure or AWS, it is not. The number of business customers is relatively small, but indirectly, the number of end users is high due to the scale.

While there’s no denying the EU has a lot to catch up upon, the grass isn’t necessarily perfect on the other side. Just last year, Microsoft stopped hiring engineers in China to work on the cloud systems of the US Department of Defense. This was done under supervision of digital escorts with a security clearance, people who merely copy pasted commands provided by the Chinese engineers, without understanding what they were doing.

We have discussed some success stories earlier, but there are many more. Nextcloud has a dedicated page to case studies. Existing European alternatives are available at european-alternatives.eu. Just to list a few we haven’t discussed:

- Open-Xchange - Email & Groupware

- Univention - Identity Management

- Gaia-X - European Cloud Federation

- Sovereign Cloud Stack - FOSS Infrastructure

- OVHcloud - a CSP from France

One of the short-term measures Europe could implement to mitigate the risks of foreign technology is the mandatory use of a software escrow. It would require non-EU vendors to deposit their source code, build documentation, and proprietary assets with a trusted third party physically located within the EU, under European jurisdiction. By mandating that the code can be released under specific trigger events, such as political embargoes, bankruptcy, or a breach of the duty of care, the EU would regain some leverage in this asymmetrical relationship. However, relying on escrow is merely a survival tactic, not a long-term strategy. Possessing the source code is one thing - having the people to maintain a massive, proprietary platform is another. It buys time to migrate to a sovereign solution, but it does not buy independence.

The Long Road to Independence

Dependency on other people, companies, or countries has always been a problem. If it wasn’t about money, then it was about power and accountability. Companies and organizations went to the cloud because it was financially attractive. In reality it makes important business processes dependent on people and companies that are merely hired. They report to others and listen to others. The practice itself isn’t new and it was well established long before the cloud became a buzzword, like AI is today. For years, it has been a habit for some decision makers to consider the financial benefit of outsourcing and being dependent more important than making the effort themselves. Therefore, we shouldn’t be surprised that they stick to that concept by pretending that they are taking enough responsibility themselves.

Awareness about the dependency within Europe is rising, but a boiling point has not yet been reached - the political will to realize real sovereign clouds and IT solutions in general does not exist yet. It is a matter of time - the more political intimidations, the sooner that boiling point will be reached. We should own our payment, web services, and security systems that function outside of the US. Do our (defense) systems have a backdoor - enabling someone to switch it off with the push of a button? Twenty, thirty years ago, that would have been a nuisance. Today, it would be catastrophic. Building a sovereign cloud is a process and it will have to happen in steps. In every step a layer of sovereignty is addressed. That of hardware and chips is perhaps in one of the last steps. We also know that the US views economic interests as national interests. They do not hesitate to leverage their information position to give their companies an advantage in commercial dealings. By building, utilizing open source and procuring locally, you also contribute to our European knowledge base. Many German, French, Spanish, and Italian governments have adopted this approach and are leading by example. The argument that we no longer have this expertise is a self-fulfilling prophecy. We have the talent and the tools. The only thing missing is the courage to change.